What are Tick-Borne Diseases?

As the weather gets warmer, you may find yourself spending more time outside. However, along with sunshine and rising temperatures comes an increase in tick activity and tick-borne diseases (TBDs). Ticks are small, parasitic arachnids found in shady, grassy areas that feed mainly on the blood of birds and mammals (e.g. dogs, horses, cows, etc.), including humans.1 Tick bites are often harmless, but infected ticks can transmit bacteria, viruses, and parasites to their host during a blood meal. Due to a variety of factors including warming climates, the number of TBDs and the geographic area occupied by ticks are growing.2,3 In 2019, the most recent year of complete data, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 50,865 cases of TBDs in the United States (US), though this is likely an underestimate due to underreporting and misdiagnoses.4 The CDC lists 16 TBDs reported in the US, including Lyme disease, Powassan virus, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and anaplasmosis.5 TBDs vary in their degree of severity, but many TBDs share similar symptoms during early stages of infection, such as fever, muscle aches, and rashes.6

Lyme Disease – The Most Common Tick-Borne Disease

The month of May is National Lyme Disease Awareness Month, an opportunity to educate the public on the transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme disease (LD). While scientists continue to discover new pathogens causing TBDs,7 LD is the most common tick-borne disease in the US, with ~35,000 reported cases and ~476,000 people diagnosed and treated for LD each year.8 LD was first identified in the 1970’s in Lyme, Connecticut, after a group of 51 residents became ill with symptoms including rash and joint pain.9 Borrelia burgdorferi, the corkscrew-shaped bacteria that causes LD, was discovered by Dr. Willy Burgdorfer in 1982.10 While LD was discovered fairly recently, it has been around much longer – scientists have even discovered a 5,300-year-old mummy who had likely been infected.11

LD is transmitted by infected deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis) after 36-48 hours of attachment to the skin,12 and is most frequently contracted in the northeast, mid-Atlantic, and upper Midwest regions of the US.12 However, reports of LD are increasing in other geographic regions.7 Symptoms for early LD resemble those of other TBDs, including muscle and joint aches, fever, headache, and chills. Notably, ~70-80% of infected individuals develop the characteristic erythema migrans (EM) rash, an often circular or bulls-eye-shaped rash that develops at the site of a tick bite after 3 to 30 days.13 If caught in its early stages, LD is easily treatable with a 2-4 week course of antibiotics. However, without treatment bacteria can spread throughout the body and cause arthritic, cardiac, or neurological symptoms.14

Diagnosing LD

A diagnosis of LD depends on a combination of a patient’s symptoms, possible exposure to ticks, and laboratory tests. If a patient has the characteristic EM rash and has visited a Lyme-endemic area, a positive diagnosis of LD can be made without further testing.15 However, not every patient with LD will present with a rash. In the case of other symptoms and tick exposure, the CDC recommends a two-tier protocol for laboratory testing.16 Methods to directly detect Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria such as PCR or culture are generally not adequately sensitive to identify positive cases of LD in early stages of infection. Therefore, testing for LD mostly relies upon detection of the patient’s immune response to the bacteria, rather than detecting the bacteria itself.15,16

Immune Response to Infection

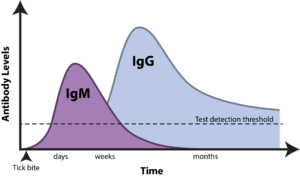

The immune system produces different types of antibodies against a pathogen at various stages of infection. In early stages, the immune response is mediated by IgM antibodies, which persist for a short period of time. As time passes, IgG antibodies dominate the immune response and can persist for years, providing extended immunity against a pathogen (see Figure 1). The presence of IgM antibodies therefore indicates the early phase of an infection, whereas IgG antibodies indicate a past infection.15

Figure 1: Timeline of appearance of IgM and IgG antibodies in response to Lyme disease.

CDC Recommended Testing Algorithm for LD

Diagnostic tests for LD rely on the detection of IgM and IgG antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria in the blood.17 Because no single test is adequately sensitive to diagnose LD, the CDC recommends using a combination of two different assays for diagnosis.15,16 The first tier of the standard two-tier testing (STTT) protocol consists of an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (i.e. ELISA or chemiluminescence assay) or immunofluorescence assay (IFA) to detect anti-Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies. If this test is positive or equivocal, results are confirmed with a second Borrelia burgdorferi-specific IgM and IgG immunoblot.15,16 In 2019, the FDA cleared the modified two-tiered testing (MTTT) algorithm as an alternative to the STTT for the detection of LD. 18,19 The MTTT consists of an EIA for screening, followed by a confirmatory EIA for detection of anti-Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and/or IgG antibodies. The STTT has a high sensitivity and specificity for disseminated LD, but the MTTT may have increased sensitivity compared to the STTT when diagnosing early-stage LD.22

Challenges in Diagnosing LD

Accurate diagnosis of LD can be challenging despite recent modifications to testing algorithms. Antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi may take weeks to develop, therefore testing for LD too early in an infection (in the first 14 days) may lead to a false-negative result. In this case, testing may be repeated on a new sample collected 7-14 days later; otherwise, further testing is not required. While IgM antibody tests can detect LD earlier in an infection than IgG tests, IgM assays are less specific than IgG tests and more likely to generate a false-positive result. 15 In addition to using a two-tiered testing strategy, healthcare providers should consider a patient’s symptoms, possible exposure to ticks, and timeline of exposure to accurately diagnose LD.

How Can I Protect Myself against TBDs?

The best way to protect yourself against TBDs is to prevent tick bites in the first place. Here are some tips 23,24:

- Know where ticks are found: you may encounter ticks during warm months, in grassy areas, and in certain geographic regions

- Cover up: wear long pants and sleeves to prevent ticks from attaching

- Use insect repellent containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus (OLE), para-menthane-diol (PMD), or 2-undecanone

- Check your clothes and body for ticks and take a shower when you return indoors

- If you find a tick, use tweezers to remove it as soon as possible 25

- See a healthcare provider if you develop symptoms and have been in tick-endemic areas

- Keep an eye out for a potential vaccine in a few years 26,27

- Don’t forget to protect your furry friends from TBDs too!

Key Takeaways

In recent years, incidence of TBDs has been on the rise. While new TBDs continue to be discovered, LD is the most prevalent TBD and vector-borne disease in the US. LD can be treated with antibiotics but has the potential to cause disseminated disease if left untreated. Therefore, accurate diagnosis of LD is vital to ensure patients receive necessary care to prevent more severe disease. While diagnosing LD can be challenging, new assays may improve testing accuracy in the future.17 In the meantime, healthcare providers should consider a combination of two-tiered testing, patient history, and possibility of tick exposure to make the most accurate diagnoses. To learn more about TBDs and how to detect them, click here to check out our past webinar on detection of tick-borne infections.

References

- Rodino KG, Theel ES, Pritt BS. Tick-Borne Diseases in the United States. Clin Chem. 2020;66(4):537-548.

- Ogden NH, Radojevic M, Wu X, Duvvuri VR, Leighton PA, Wu J. Estimated effects of projected climate change on the basic reproductive number of the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(6):631-638.

- CDC. Understanding Lyme and other tickborne diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/media/lyme-tickborne-diseases-increasing.html. Published 2022, May 11. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- CDC. Tickborne disease surveillance data summary. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/data-summary/index.html. Published 2022, August 11. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- CDC. Diseases transmitted by ticks. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/diseases/index.html. Published 2022, March 4. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- CDC. Symptoms of tickborne illness. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/symptoms.html. Published 2021, August 5. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- Madison-Antenucci S, Kramer LD, Gebhardt LL, Kauffman E. Emerging Tick-Borne Diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;33(2).

- CDC. How many people get Lyme disease? https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/humancases.html. Published 2021, January 13. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- Steere AC, Malawista SE, Snydman DR, et al. Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three connecticut communities. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20(1):7-17.

- Burgdorfer W, Barbour AG, Hayes SF, Benach JL, Grunwaldt E, Davis JP. Lyme disease-a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science. 1982;216(4552):1317-1319.

- Keller A, Graefen A, Ball M, et al. New insights into the Tyrolean Iceman’s origin and phenotype as inferred by whole-genome sequencing. Nat Commun. 2012;3:698.

- CDC. Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/transmission/index.html. Published 2023, January 20. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- CDC. Signs and symptoms of untreated Lyme disease. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/signs_symptoms/. Published 2021, January 15. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- Lantos PM, Rumbaugh J, Bockenstedt LK, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(1):e1-e48.

- APHL. Suggested reporting language, interpretation and guidance regarding Lyme disease serologic test results. https://www.aphl.org/aboutAPHL/publications/Documents/ID-2021-Lyme-Disease-Serologic-Testing-Reporting.pdf. Published May 2021. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- CDC. Diagnosis and testing. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/diagnosistesting/index.html. Published 2021, May 21. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- EUROIMMUN. Tick-borne infections. https://www.euroimmun.com/products/infection-diagnostics/id/tick-borne-infections/. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- FDA. FDA clears new indications for existing Lyme disease tests that may help streamline diagnoses. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-clears-new-indications-existing-lyme-disease-tests-may-help-streamline-diagnoses. Published 2019, July 29. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- Auwaerter PG, Kobayashi T, Wormser GP. Guidelines for Lyme Disease Are Updated. Am J Med. 2021;134(11):1314-1316.

- Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(31):590-591.

- Moore A, Nelson C, Molins C, Mead P, Schriefer M. Current Guidelines, Common Clinical Pitfalls, and Future Directions for Laboratory Diagnosis of Lyme Disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(7):1169-1177.

- Sfeir MM, Meece JK, Theel ES, et al. Multicenter Clinical Evaluation of Modified Two-Tiered Testing Algorithms for Lyme Disease Using Zeus Scientific Commercial Assays. J Clin Microbiol. 2022;60(5):e0252821.

- Richardson M, Khouja C, Sutcliffe K. Interventions to prevent Lyme disease in humans: A systematic review. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:16-22.

- CDC. Tick bites/prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/tick-bites-prevention.html. Published 2022, August 5. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- CDC. Tick removal. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/removing_a_tick.html. Published 2022, May 13. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- Moderna. Moderna announces clinical and program updates at 4th vaccine day. https://investors.modernatx.com/news/news-details/2023/Moderna-Announces-Clinical-and-Program-Updates-at-4th-Vaccines-Day/default.aspx. Published 2023, April 11. Accessed 2023, May 5.

- Pfizer. Pfizer and Valneva issue update on Phase 3 clinical trial evaluating Lyme disease vaccine candidate VLA15. https://www.pfizer.com/news/announcements/pfizer-and-valneva-issue-update-phase-3-clinical-trial-evaluating-lyme-disease. Published 2023, February 17. Accessed 2023, May 5.