Oropouche fever is an emerging arboviral disease caused by the Oropouche virus (OROV). Recently, OROV has sparked health concerns due to a spike in cases seen in the Americas, the first confirmed OROV-associated deaths, and reported transmission from pregnant mothers to their babies.1 The virus was first detected in a forest worker from Vega de Oropouche in Trinidad and Tobago, near the Oropouche river, in 1955 and has since been endemic to Amazonian regions in South America. Recent outbreaks and its expansion into ecosystems outside of the Amazon Basin in the Americas have prompted the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) to publish guidance on detection, surveillance, and reporting in these regions.2,3 Importantly, as of October 1st, 2024 there have been 90 reported travel-related Oropouche infections (2 neuroinvasive), with reports also seen in Canada and Europe.

The sudden outbreak affecting nearly 8,000 Brazilians and subsequent spreading to other countries such as Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Canada, the United States, and Europe has brought confirmed cases to nearly 10,000 and counting in 2024.1 For context, from 2015 to 2022, only 261 cases of Oropouche virus were recorded in Brazil.4 Health agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), are emphasizing the need for continuous monitoring of OROV infections, especially as cases in North America rise.2 Accordingly, there exists a great need to strengthen surveillance and preparedness actions including investigating cases associated with fetal death and neuroinvasion. Furthermore, early symptoms and detection of the virus are critical for controlling the spread of this disease, making diagnosis and testing essential tools in managing the increasing number of cases.

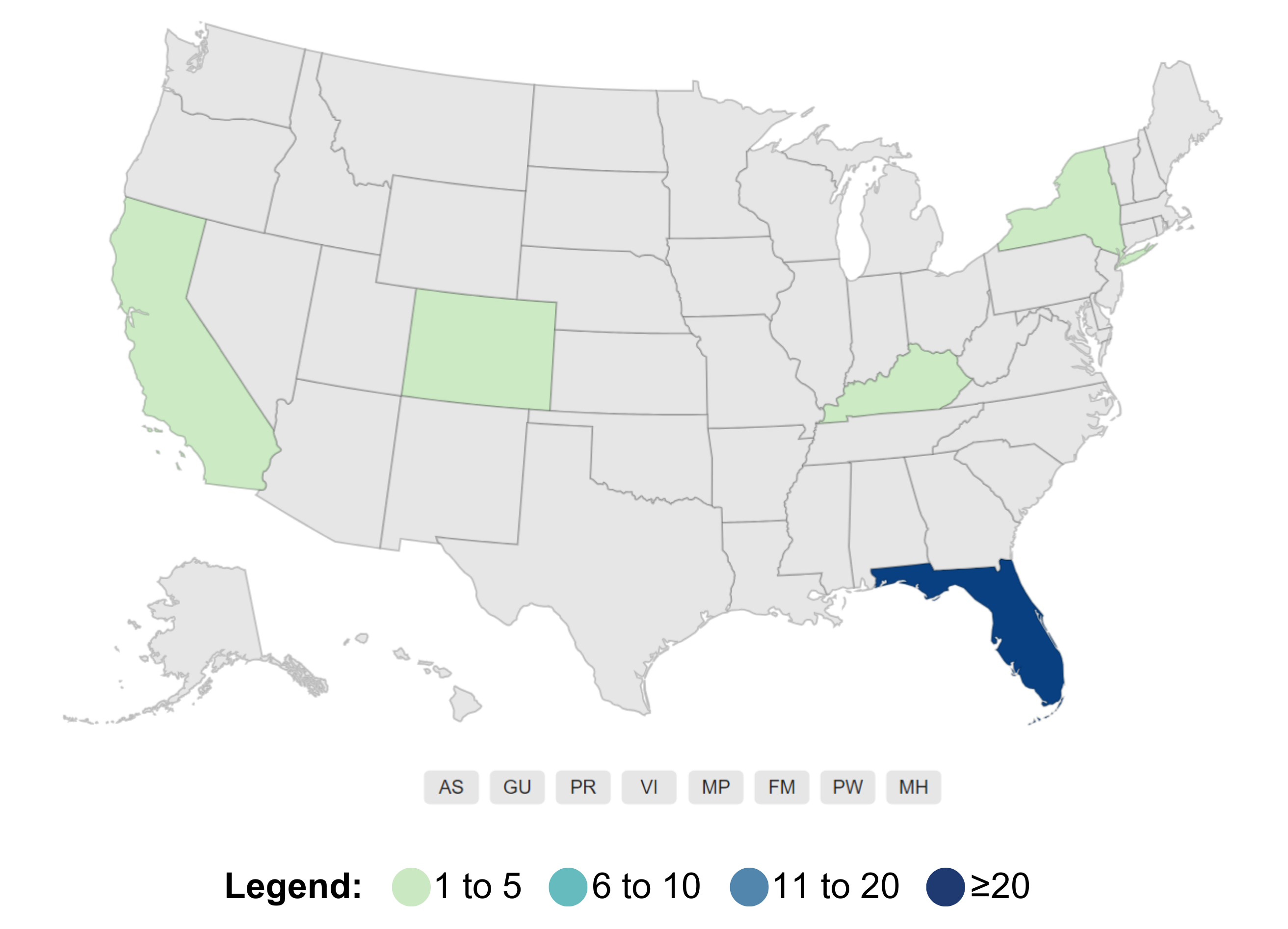

Number of travel-related OROV cases in the U.S. as of October 1, 2024, reported by state of residence. Source: Current Year Data, CDC

Number of travel-related OROV cases in the U.S. as of October 1, 2024, reported by state of residence. Source: Current Year Data, CDC

What is Oropouche virus? Transmission, clinical symptoms, and disease

Arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) include many viral families which infect humans primarily through the bite of a blood-feeding arthropod vector such as mosquitoes, ticks, and biting midges, or sand flies. Oropouche virus belongs to the genus Orthobunyavirus. OROV, in particular, is transferred to humans via the pesky biting midge, Culicoides paraensis, which have been identified in tropical and subtropical areas across the Americas.5 While less common, OROV can also be transmitted through the southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus), which is known to be present in Florida. The main concern is that any infected individual can generate a local epidemic. In the past, we have seen periodic, explosive OROV epidemics in Brazil and surrounding countries resulting in well over 500,000 infected individuals to date. If OROV were to spread in tandem with other common arboviruses, such as Dengue or Zika, which present with similar clinical symptoms, it could overload health services in the affected countries, further highlighting the need for accurate testing and prevalence studies.

Symptoms include abrupt onset of high fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, joint pain/stiffness, and persistent nausea and vomiting for up to 5 to 7 days. Additionally, infected individuals can present with retroorbital pain, sensitivity to light, rashes, and in severe cases, neurological manifestations such as meningitis or encephalitis. In most cases, OROV presents as mild to moderate, generally resolving itself within 2-3 weeks without long-term effects, but relapses can occur in up to 70% of people during the first week after symptoms disappear.5,7

Diagnosis and Treatment

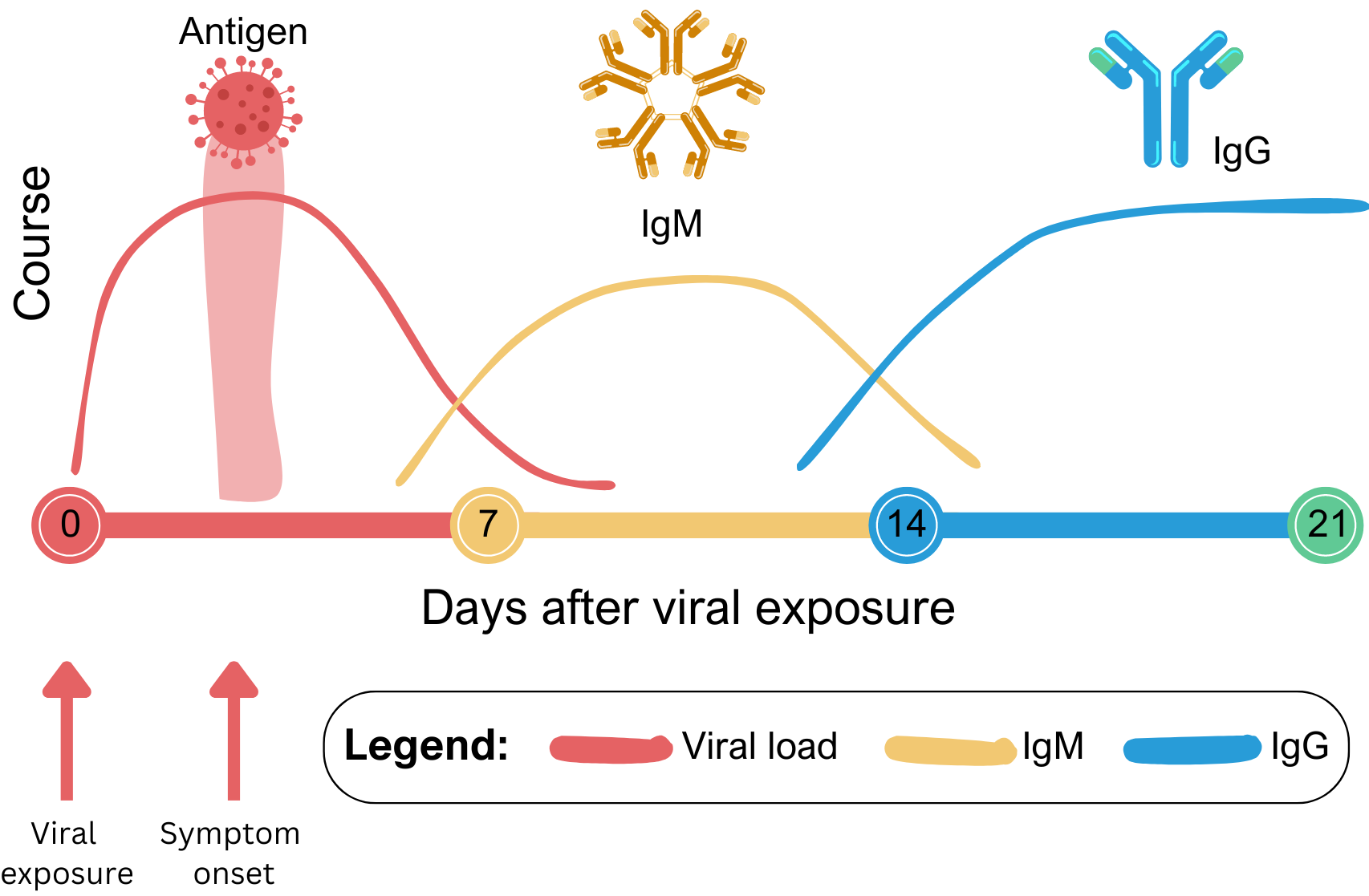

Oropouche fever cannot be diagnosed based on clinical symptoms alone, as they are similar to those of Zika and Dengue, which are transmitted in the same regions. Therefore, laboratory testing is crucial. In the early phase of infection (up to 7 days after symptom onset), molecular assays like the polymerase-chain reaction (PCR) to detect the virus (RNA, genetic material) is the preferred diagnostic method.2,3,8 In PCR, even if the virus is present in very small quantities, many copies of its genetic material are made, and results are available in just a few hours. However, after seven days the virus is no longer detectable in the blood, making antibody detection crucial for painting the full picture on OROV infections. After infection with any virus, our immune system gets to work producing different types of antibodies to protect us from future infections (see image below). IgM antibodies appear first for a short period, followed by IgG antibodies, which persist for many years, as in other infectious diseases. ELISAs (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) utilize Oropouche-specific IgM or IgG proteins (antigens) to capture antibodies that an infected patient’s blood sample might contain. Accordingly, if antibodies are present, a reaction will occur that produces a measurable color-change. Testing for IgG, which is a marker for late-phase or past infection, is especially important in gathering prevalence information on OROV, which can inform surveillance and influence both subsequent guidelines and enactment of preventative measures amongst the public.

Timeline illustrating viral load and antibody levels after a general viral infection.

Timeline illustrating viral load and antibody levels after a general viral infection.

Due to large outbreaks in Brazil and travel-related Oropouche cases reported in other countries, the CDC, public health laboratories, academic institutions, and commercial manufacturers have responded swiftly by developing assays to aid in diagnosis and conduct prevalence studies—where previously, no commercially available assays were available.

Unfortunately, there exist no vaccines or antiviral drugs to prevent or treat OROV infection. Managing the disease is symptomatic, and focuses on controlling fever, relieving pain, hydrating, and controlling vomiting, if present.1

Recent progression and future perspectives

Oropouche is surpassed only by dengue, taking the crown as the second most frequent arbovirus in Brazil. Due to recently alarming changes in clinical and epidemiological characteristics of OROV, including vertical transmission, neuroinvasion, first recorded fatalities, and possible association to fetal death—the importance of conducting additional research, reinforcing preventative measures, and protecting vulnerable populations like pregnant women, their fetuses, and newborns cannot be overstated.1,4,9 The CDC suggests various methods to avoid insect bites, and to reconsider travel to certain areas in South America until we collect more information regarding OROV’s poorly understood epidemiology, pathogenesis, and natural history.10

References

- PAHO. Epidemiological Update Oropouche in the Americas Region – 6 September 2024 – PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization (2024).

- PAHO. Guidelines for the Detection and Surveillance of Emerging Arboviruses in the Context of the Circulation of Other Arboviruses – PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization (2024).

- PAHO. Recommendations for the Detection and Surveillance of Oropouche in possible cases of vertical infection, congenital malformation, or fetal death – PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization (2024).

- Martins-Filho, P. R., Carvalho, T. A. & Dos Santos, C. A. Oropouche fever: reports of vertical transmission and deaths in Brazil. Lancet Infect Dis, doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00557-7 (2024).

- Romero-Alvarez, D. & Escobar, L. E. Oropouche fever, an emergent disease from the Americas. Microbes Infect 20, 135-146, doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2017.11.013 (2018).

- Maria Paula G. Mourão et al. Oropouche Fever Outbreak, Manaus, Brazil, 2007–2008. Emerging Infectious Diseases 15, 2063-2064, doi:10.3201/eid1512.090917 (2009).

- Raimunda do Socorro da Silva Azevedo et al. Reemergence of Oropouche Fever, Northern Brazil. Emerging Infectious Diseases 13, 912-915 (2007).

- CDC. Updated Interim Guidance for Health Departments on Testing and Reporting for Oropouche Virus Disease | Oropouche | CDC (2024).

- PAHO. Public Health Risk Assessment related to Oropouche Virus (OROV) in the Region of the Americas – 3 August 2024 – PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization (2024).

- CDC. 2024 Oropouche Outbreak | Oropouche | CDC (2024).